Sikandar now reached beyond the edge of the world for the fourth or fifth time. In each land he left husks of himself, vomiting up cities and rivers like sloughing off fine dead skin. With the invasion rumbling on, spoil flowed down back to the mainland on great wooden barges manned by Egyptians. Sikandar strained against nostalgia and pushed his best men forward, a hardened core of a few thousand. He rocketed like a javelin, which was already whittled down from a great trunk to pierce the air, and which now lost its last rings, burning up into a thin needle. Now he stunk of rotten meat, his army was cut like stone and he limped sword-hand first.1

Sikandar refused to blow himself out and his project continued a ghost expedition shimmering on through Asia. They still arrived at small towns frequently. In this land the guides they picked up some months ago from the defeated King Porus could still barely bridge the limits of language.2 But Sikandar, his trajectory incomprehensible, could give no reason for why he came here. In time he lost the ability to explain himself entirely, and his army mutinied over and over, but each time they were shackled again to this great unspeakable entropy.

At first the oracle at Siwa venerated Sikandar, now they all did. He was proclaimed a God by Dodona – the oldest of oracles, the Pelasgian tree of Zeus. He speaks through rustling bronze chimes. A priest interprets this answer and gives responses. The naïve regard this as malfeasance, the intervention of a mediator, who deifies himself through deception. In truth, the oracle is a projection of consciousness of the greatest sort. Men are with mind and soul, and it all spills out from them into everything in every grunt and flex. A thing filled with consciousness has its own life. Who can say where it comes from? But whatever is unspeakable, that we call Zeus.

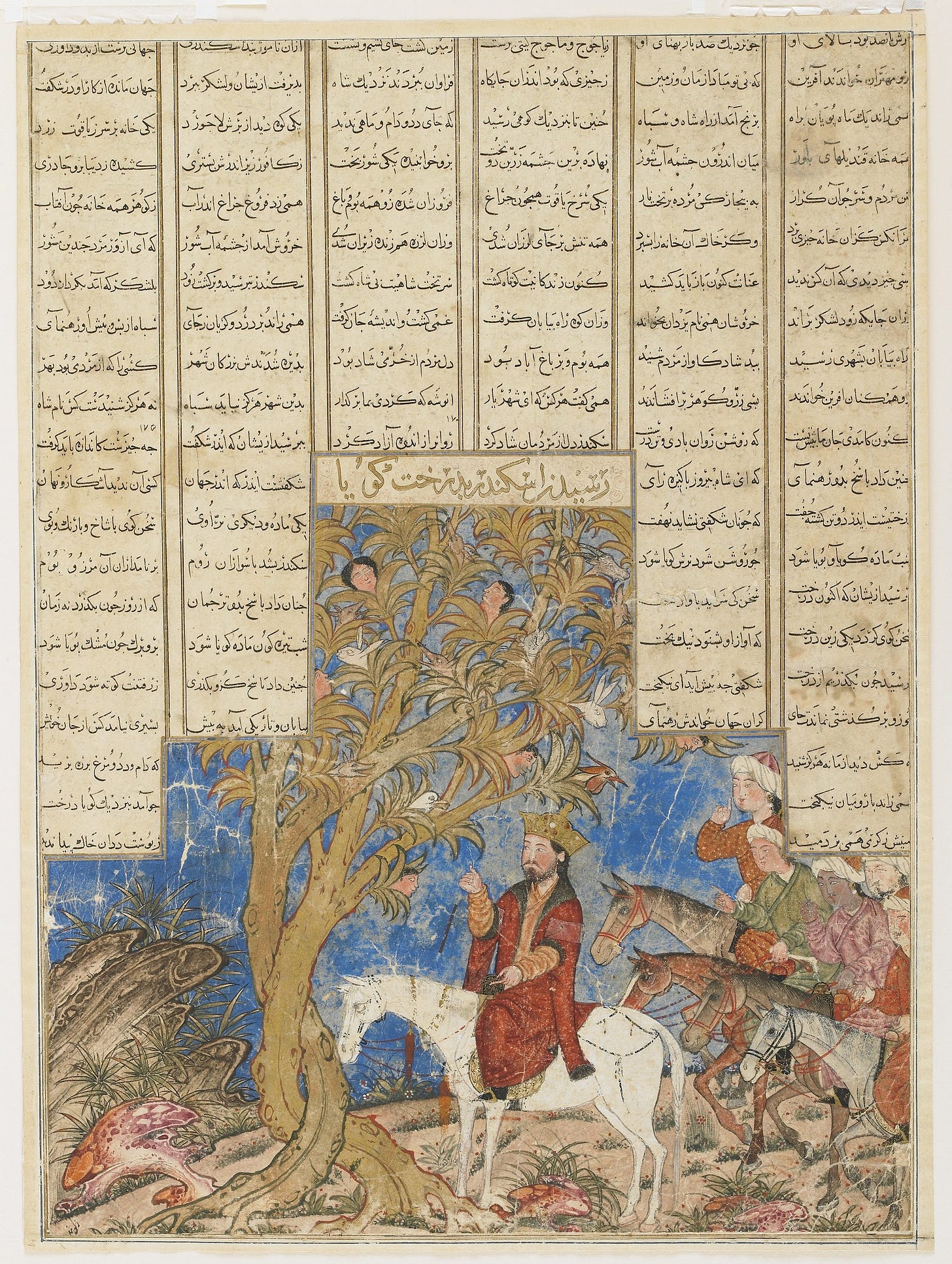

Reaching a town, he received some direction from the people. Stood side by side, the military men picked up all along Sikandar’s excursion and the denizens of the town weren’t aliens to one another, but in their hearts there was nothing to express, nothing that could be shared. Everything Sikandar could give and take was years behind. They told him that some days’ march away there was a great sacred forest. This was greater than the tree at Dodona which was Zeus’ voice: a whole forest full of God, which spoke to men and told their fate. There was no temple, no priest to interpret the words, but the village sent with him a young man to guide the way. Sikandar resolved to make conversation with the forest and enquire about his fate.

On the march, the young man, who had great olive thighs and curly black hair, almost as beautiful as Hephaistion, spoke to Sikandar.

“Why are you in this land, king?”

“To stretch the limits of glory”.

“What does that mean?”

“I go beyond what any mortal has done, scouring new worlds”.

“New? My father walked these hills too”.

“No Greek has been here. For a man to go so far in life is impossible. For this they deify me”.

“You’re a God?”

“I was born from one. The oracle told me”.

Sikandar thought the young man seemed unimpressed; he was slightly embarrassed. They continued for a while in silence before Sikandar spoke again.

“Have you heard the story of the philosopher and I?”

“What’s that?”

“I wished to test a philosopher, the greatest in the realm, to see what he could see. I conversed with him through gifts, back and forth, neither of us uttered a word”.

“Why would I have heard that?”

“First I sent him great riches. He sent them back. Then I sent him precious metal, moulded into pins. He melted them into a disc and sent it to me. I left it to rust. He sent it back polished to a mirror sheen, dipped in a solution that guards against further rot. Of course, I confirmed with him afterwards that he had understood me. Do you understand?”

“I suppose. Can’t either of you write?”

Sikandar smiled. The youth reminded him of himself as a young boy. He remembered how once he tormented his mother by laughing all day. At her, at the chambermaids, at guests of the palace. She kept telling him: “Stop it! Stop it! Do you want a slapped bum?” He continued to laugh, not acknowledging her. She cried out “You’ve misbehaved the whole day!”. He continued to laugh, and finally got a smack – a prince never gets smacked. He spent the rest of the day crying for his daddy, the King.

“I can write quite well, actually. But the philosopher – he’s a Cynic, the great Onesicritus. How would you say it here? An ascetic. Writing is not for him.”3

“Ah! Onesicritus, I’ve heard of him.”

“Really? How’s that?” Sikandar admitted his jealousy to himself.

“Well, he’s nothing impressive himself, but he met the great Dandamis, the guru.”

“Oh yes, you’re right. I sent him myself-”

“To demand the man come speak to you! A sage and Brahmin. What an ego.” The young man scoffed at Sikandar for his petulance.

“His response was much the same. In fact, I told him I was a god too.”4 Sikandar brushed the boy’s tone off with an airy, reflective gaze.

“And his response rings true: gods do not do violence, and they do not demand. Whatever we call god, is what gives us all that is good.”

“My own teacher told me something similar: that behind all things there is an ultimate cause, and that cause is god. God accomplishes everything, he ends every sentence: so, to do violence is not to be separate from god. It is to make the things of this world submit to a higher end, to give them purpose in accomplishing a loftier plan.”5

“God does not self-mutilate. There is no good in a wound, that wound is only pain. What you describe – it is to fall from god’s plan by your own volition.”

Sikandar took a swig from his hipflask. He was now certainly interested. He intended to make the boy his lover, to carry him within their expedition and make him a new Hephaistion. He would eat the boy whole. The young man, for his part, resolved to kill Sikandar by any means necessary.

Red crags and hard dirt, punctuated by wisps of wood and leaf, gave way to forest. Leaving his army to camp and rest, he entered the forest with the young man as his guide. Sikandar, always praised for his erudition in youth, brought with him a set of scrolls, his Iliad, which at night he would sleep atop of.

Sikandar thought that the trees that reached the ceiling, floating in cold fresh air, if only they were closer, if they weren’t so far – he had strayed so far – they would flow back caught on his current, becoming warships, shelves – a great library in his great city – lumber, firewood, a permanent presence; but they were imprisoned by distance far beyond anything, for some other people to pluck. His acquisitions were long impossible, a glide of the fingertips that couldn’t become a grasp, like scalding water becoming smoke. They would stay here and be lost in a strange land. He could make no gift of them.

Sikandar thought to make conversation with the forest. Guided by the intuition that felled empires, he rapped his knuckles against bark and broke small branches off the trees. As they wandered in a new rapture, the boy contented himself in picking flowers from the forest’s floor. Wandering, Sikandar seemed led in strange directions, and unnoticed by him, if a hawk or God flying high above were to see the forest, they would see it coiling in nautilus shells, breathing in its splendour, and forming here a maze, here an enclave. But the world had not yet been seen from the sky. By now his guide had already vanished, but Sikandar did not notice.

The forest had denizens: muntjacs and serows, men with the faces of lizards and sages who knew the mysteries of the Godhead. Sikandar saw a muntjac and thought it a comical animal: a plump little deer, with curved horns popping out of furry protrusions on its forehead. Those protrusions, its pedicels, looked to be made of felt, or some condensed itchy wire, the sort that makes up a toy that a child can’t bear to hold. But the child can’t let go of it either, since he still knows his kinship with a friend – only in adolescence does the thing lose its soul, the man sucks it up like marrow. The muntjac’s frumpy tail hanging like a bauble, and its ginger taint, brightest on its neck and flowing down its hunched back – now they can be seen in South East England, where they enjoy hedgerows and the embankments of railways. Introduced from China, they are now a bane to the honeysuckle and orchid, and to the gardener who wishes everything to proceed from his precise design.

Sikandar went to ask his guide which creature was this and noticed only now that the boy had disappeared. He was distraught. He thought the boy must be lost but knew in his heart that he had been thrown off like the rider from the bull. But the bull is not content to throw men off, it must next gore them with its horns curved like lyres.

In the forest, too, is datura, the death-bringing flower. It is also the flower that some men say is consumed by the priestesses at Delphi, where they speak the words of god. But again, those who tell such stories about oracles are fools. This plant is changeable like the wind, and whether it is for ill or good, only the seasoned can tell, from its age and the colour given off in the sky. Local shamans use it still to this day, since shaman gods kidnap boys from villages to pass on their rites.6 The boy, not unfamiliar with the witching arts himself, ground the plant up with other forest herbs, and sprinkled it in Sikandar’s flask, where mixed with wine (the young man could smell the unmixed wine emanating from his breath, the drunkard) it would be sure to kill. He would defend his land from the interloper and his thugs.

As Sikandar wandered the forest, he quenched his thirst. Sikandar felt that some force led him up a dried-out creek, and grappling up rocks and dead river plants he became ashy and covered in soot. His wet hair was caked to his head and he felt the ache in his wounds. At the top, the forest said nothing to him. He now thought to leave his scrolls of Homer to the forest: he left scrolls by a number of the trees nearby him.

In the era before other life there was no decomposition. Piles of leaves buried the soil yards deep like snow cover. The trees laid this carpet over the glades, burying themselves in excrement. Relief came only with fires that spanned eons and wrecked continents ripping up all the dead skin of the forest like everything was sunk into a boiling hot bath. In time the ash gave rise to a new race which ate the ground and there was now a pact between beings. Ever since it has been upheld: everything you leave us, we will take, and we will rip your bark and leech your sap. But you will have dignity and die and we will finish you off.

When one journeys again through the place they were born, they encounter a sensory affliction: each silhouette of a particular cadence, each tussle of hair and yell, could belong to one they grew up with, which fills the recipient with terror. Sikandar was called Sikandar in one land, Al-Eskandar in another, and also Alexandros. These exonyms overlapped him creating a no-man’s-land of nominative being, claimed by all and none. The soul is miniscule – in the span of a whole life it can only cross the gap between life and death. All other movements are grasping and meek.

Sikandar had re-remembered himself many times, each time his new self stood atop new enemies, and now he was the son of a God, the brother of Darius, the husband of Roxana, the lover of Hephaistion, who was dead, and he was not at all who he was who was born on the same day as a horse, who lived and died without remembering anything. He had burnt memory and become abstract, a name in a book, on his final quest through moth-bitten volumes, in a library to be rediscovered in a new golden age, where he would renew his conquest, forgetting himself again.

Sikandar now felt keenly that he would die. The night drew cold, he let out a shiver. The forest spoke nothing, its silence was a remark. It was dark and he was alone, so he left. He felt denied, and wanted only to sink home, to return to his parents – past the oracle, to his mortal parents, and he was covered in ash and spores. The poison did nothing to him – Sikandar became immune to most poisons long ago. He had drunk unwatered wine mixed with the poisons of every land. An immortal such as him would not succumb to it. But on leaving the forest, he marched his army home for the first time.

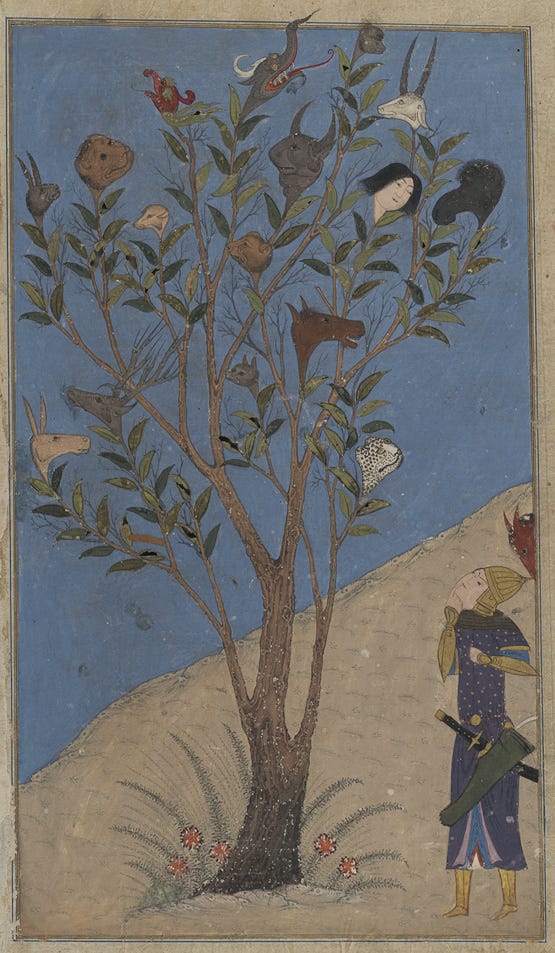

The land would venerate the olive-skinned young man who had vanished. In cult, he had repelled a great king from the West, a shaman in alliance with the spirits of the forest. He fought his guerilla war and became one with the trees, his final reward. His cult would survive for generations, and by the time of the great 10th century Shahnama, the Persian epic, he would be remembered as the two-trunked tree who prophesied Sikandar’s death. One trunk was male and spoke by day, the other was female and spoke by night, telling the king that in a matter of months, he would be dead.

Sikandar met his fate in Babylon; he would never again see home. He lapsed into a paralysis unto death. To all he seemed dead, but in truth he still lived, succumbing to a condition that imprisons man between life and death – now it is known as a disease which traps consciousness within a dwindling body. He was not locked in, rather he forgot his body and himself. He floated incorporeal as we do upon waking, before our first breath is drawn, a knot of tendons connected only in name. He was like the Pyrrhonian sage, who according to the Stoics is a man who has rid himself of belief and all bodily commitments towards belief, and he sits lucid in a heap. His muscles don’t know to keep upright or draw further breaths, and he is jelly on the ground, sinking into whichever arms will hold him. He lay dead like a child. His compatriots argued, prayed, and some wept, or schemed for an empire of their own. Whichever land would bury the man, its king was sure to rule. Ptolemy brought the body in a great cypress bier down rivers and roads accompanied by a small army to its new home in Alexandria, a new home for the king, before the body was lost on the road and lay there still living, refusing to decompose in the dust and sun.7

In ancient geography, the world’s rationality declines throughout space according to a centrifugal law: with distance from the whirring civilised centre, the world becomes increasingly incoherent. Herodotus provides a relativisation of this principle, which accomplishes for anthropology what general relativity does for physics – each people is a centre in themselves, making the Greek centre itself an incoherent periphery for far-off cultures. The indeterminate space beyond the edge of the known world is a realm of speculative mythology for the Greeks: Euhemerus, for instance, reasoning that the gods must once have been mortals, invokes an island past the Arabian Peninsula, upon which the gods ruled as mortal kings, before history and beyond the world. Alexander sought immortality also, in lands beyond the known world.

Alexander, following his victory over Porus, recognised him as a fellow king. Porus was appointed satrap of an expanded territory including his original kingdom. The position of satrap was retained from the organisational structure of the defeated Achaemenid Empire and designated an autonomous regional ruler invested with the king’s authority. Local guides retained from Porus’ capital Kangra Fort were most familiar with Sanskrit and the Prakrit languages (vernacular dialects of Sanskrit) spoken in the surrounding lands, particularly Paishachi Prakrit, which would later become Punjabi. In Northeast India languages within the Tibeto-Burman, Indo-Aryan, and Kra-Dai families were spoken. This was among the territories later controlled by the British Raj, which designated it as part of Bengal Province.

Onesicritus, the Cynic philosopher, accompanied Alexander’s expedition as pilot of his ship. He was criticised in ancient times for purporting to be commander of the fleet. His account of Alexander’s adventures, written later in life, was also roundly criticised in antiquity for its fabulism, reporting among other fictions a meeting between the King and the Amazons.

Dandamis, an ascetic philosopher encountered by the Greeks in the woods near Taxila, Punjab. Dandamis refused to come meet the king, despite threats and declarations of divinity delivered by Onesicritus. When Alexander came to him instead, Dandamis spoke these words: “If you, my lord, are the son of god, why - so am I. I want nothing from you, for what I have suffices. I perceive, moreover, that the men you lead get no good from their world-wide wandering over land and sea, and that of their many travels there will be no end. I desire nothing that you can give me; I fear no exclusion from any blessings which may perhaps be yours. India, with the fruits of her soil in due season, is enough for me while I live; and when I die, I shall be rid of my poor body - my unseemly housemate." Alexander made no further attempts to compel the man and left.

Alexander’s teacher was Aristotle, who developed arguments in favoured of the ‘unmoved mover’ – an ultimate cause at the bottom of all other causal chains. This argument avoids a regress of causes stretching back into infinity.

Banjhākri and Banjhākrini. Banjhākri takes children who may become shamans and trains them. Banjhākrini, the bear goddess, might eat the child if she does not approve of them. A shaman who Banjhākrini approves of, and who Banjhākri trains, is more dangerous than any other.

Dr Katharine Hall of the Dunedin School of Medicine proposes that Alexander the Great suffered from Guillen-Barre Syndrome, a disorder in which the immune system attacks the body’s own peripheral nerves. In fighting an infection, the body can mistakenly target itself. Starting with numbness in the peripheries, the immune system wages a war advancing inwards. The body destroys its own facial muscles, and sometimes the muscles controlling the bladder and anus. In its final stages the paralysis reaches the respiratory system. In time, all nerves outside the brain and spinal cord are destroyed. Alexander’s breathing would have become reliant on the imperceptible movement of air driven by the remaining strength in his neck muscles. Death, in ancient times, was diagnosed by the cessation of movement in the chest, not by the absence of a pulse. The king’s dead body, its heart still beating, did not decompose. This was taken in ancient times as evidence of Alexander’s ascension to godhood.

Absolutely fantastic